Behind the shifting, steel-grey sea

Beyond the cliff-top fringe of golden-flowered gorse

Between the twisted, wind-sculptured thorns...

I saw a tapestry of little green pastures

Stitched together by a thick thread of hedges:

Like a quilt of soft turf draped over

The old bones of a sleeping giant.

Tuesday, 2 December 2014

Tuesday, 25 November 2014

Crow-King and Red-Bead Woman

After hearing the story of the Crow-King and the Red-Bead Woman told by Martin Shaw, I walked around Allington Hill and found images of the story everywhere I looked...

By the edge of the hill, beyond

the edge of the town, through the old gate, is a patch of waste ground – thickly covered

with brambles and burdock, but recently cut to carve out a rugged meadow; revealing,

and releasing, five suckering elms. Back to life from beetle-borne demise, the trees,

in the first flush of restored youth, already carry within themselves their own

seeds of destruction: as soon as they grow bigger, and their sap-wood

thickens, the deadly disease will return. Re-birth and re-death re-cycling in a

single surviving species…

I follow a trail of fallen golden

leaves, hawthorn and hazel, gleaming in the dull mud, until the tantalising track

leads me to the scurrilous scarlet hues of a sweet chestnut; its russet, serrated

leaves quivering like nervous creatures. Without lowering my eyes, I hurry on in case a cold

wind should shake the leaves from the branches and strip the beauty from the tree.

A black springer spaniel suddenly appears on the path in front of me, materialising from the autumnal mist. It stands and stares, sniffing the air between us, as we contemplate each other’s existence with natural neutrality. A high-pitched whistle breaks the spell and the dog is recalled to its owner, leaving me to recall on my own. The shift of focus discloses the last mouldering remains of blackberries on a big bramble bush beside me. Amongst clumps of stalk-stumps, picked clean by the birds, there is one last intact drupelet. I pluck the soft piece of fruit-flesh and pop it on my tongue; its fragrant, fertile fidelity finds a haven of warm, soft sensitivity in my mouth.

At a fork in the path I pause to listen to the blue-tits singing in the trees – the longer I stand still, they bolder they become, eventually just a few feet from my face. Then they scatter and scold as I make a move to choose my route: not the wide, grassy, uphill path, but the narrow, winding, downhill one, through the beech woods. Descending is difficult, harder than going up, the sloping terrain pushes me faster than I want to go, whilst my resistance and recalcitrance makes my legs stiffen and my feet slide uncontrolled; hard angles against the soft contours of the land.

A black springer spaniel suddenly appears on the path in front of me, materialising from the autumnal mist. It stands and stares, sniffing the air between us, as we contemplate each other’s existence with natural neutrality. A high-pitched whistle breaks the spell and the dog is recalled to its owner, leaving me to recall on my own. The shift of focus discloses the last mouldering remains of blackberries on a big bramble bush beside me. Amongst clumps of stalk-stumps, picked clean by the birds, there is one last intact drupelet. I pluck the soft piece of fruit-flesh and pop it on my tongue; its fragrant, fertile fidelity finds a haven of warm, soft sensitivity in my mouth.

At a fork in the path I pause to listen to the blue-tits singing in the trees – the longer I stand still, they bolder they become, eventually just a few feet from my face. Then they scatter and scold as I make a move to choose my route: not the wide, grassy, uphill path, but the narrow, winding, downhill one, through the beech woods. Descending is difficult, harder than going up, the sloping terrain pushes me faster than I want to go, whilst my resistance and recalcitrance makes my legs stiffen and my feet slide uncontrolled; hard angles against the soft contours of the land.

In the deep woods, the harts-tongues,

the spirits of the place, speak in leafy green words - their own fern-acular - but I cannot comprehend

their wild whisperings, nor do I heed their warnings. Suddenly my coat catches on the inch-long spines of a

blackthorn bush sprawling across the path. After unhitching myself, I look

closer at my barbed assailant: the dark-purple limbs have twisted together,

rubbing against each other, to cause cankers and callouses in the bark. The rotting,

suppurating lesions are being steadily eaten by a slowly writhing mass of glistening

grey-brown slugs – feeding on the trees own wounds, its weakest, most intimate

parts. Or perhaps these are the vegetation’s medicinal leeches…

From the threshold of the forest

I can see and hear the village across the valley, but its vision and sounds are

disturbed, disconnected, by the distant, incessant roar of the road cutting through the

landscape. As I walk out from the thinly-leaved canopy of the trees, cold rain

falls on my head – intentionally un-hooded I let the icy drops sting my skin, drench my hair and refresh my

thoughts. At the top of the escarpment, on the oddly angular branch

of a blue-green pine, is a raven: the king of the crows. His call, harsh and

heavy, rolls down onto lush leafy slopes below. There, in the green court of the

king, stands a holly queen: her crown of thorns threaded with strings of coruscant red

beads. As I walk back to the beginning, through the meadow of broken brambles, on

the edge of the hill, I notice that amongst the re/de-generating elms is an adventitious oak

sapling, born from a single seed, aspiring to be old.

A link to Martin Shaw's re-telling of the tale: http://greatmotherconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/CROW-KING-2014.pdf

Tuesday, 28 October 2014

The White Stag

A self-penned song inspired by the colours of autumn, a white stag seen roaming Dorset recently and a plucky girl I know called Annie...

Annie went walking out one day

Where she was going - none could say

The rain did fall and the wind did blow

But it didn’t bother Annie as off she did go.

She walked for a mile and she walked for more

‘Til her legs were tired and her feet were

sore

She came to a forest both deep and old

Where the leaves there were turning green to gold.

Underneath the canopy of trees she did tread

Her boots were brown and her clothes all red

She came to a glade with light all around

There she saw a white stag - sleeping on the

ground.

Annie crept closer to the deer

She stroked his head and whispered in his ear

The stag then he sturted, and away he ran

With Annie chasing after; as fast as she can.

The path was steep and the way was narrow

The white stag was flying as fast as an arrow

Annie she followed but Annie she fell

She twisted her leg and hit her head as well.

She slept through the day and all through the

night

Into her dreams a young man came, all dressed

in white

He kissed her and he held her in his arms

And said: “Annie, will you ride with me?

You won’t come to harm.”

Through the green and golden forest those two

did ride

The white stag beneath and the red girl

astride

They rode ‘til they came to the edge of the

trees

And now Annie’s crying as she watches him

leave.

Annie went walking out one day

Where she went - she never would say

The rain did fall and the wind did blow

But it didn’t bother Annie where she did

go.

Tuesday, 21 October 2014

Thursday, 9 October 2014

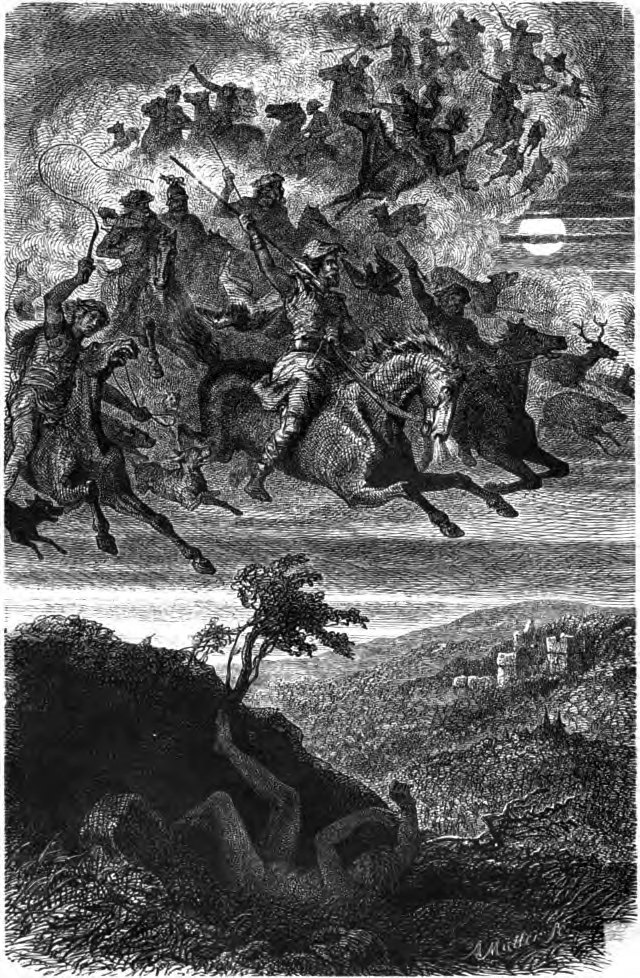

The Wild Hunt

The thunder of hooves

The lightening crack of a whip

The baying breath of dogs

Misting the autumn air

The haunting sound of hunting horn

The inciting scent of unseen prey

The flash of wild, white eyes

The straining of unbridled steeds

Pulled by the moon’s momentum

Swirling in vertices of velocity

Drumming the taught earth

Then piercing the night sky…

The broken branch

The indented earth

Flying leaves and scattered seeds

Fleeing feet and clattering wings

Racing heartbeats slowly receding

Monday, 6 October 2014

Autumn tuning

Outside it's wild and wet

And windswept

Brown leaves blown

In clusters of blusters

Whilst the moist, mouldering earth

Slowly sucks back

Springtime promises

And summer profligacy.

Indoors it's dark in the daytime

As I withdraw within, mulling:

Underneath the mush of this year's leaves

Next year's seeds are already sown.

And windswept

Brown leaves blown

In clusters of blusters

Whilst the moist, mouldering earth

Slowly sucks back

Springtime promises

And summer profligacy.

Indoors it's dark in the daytime

As I withdraw within, mulling:

Underneath the mush of this year's leaves

Next year's seeds are already sown.

Friday, 26 September 2014

The Legend of the White Hare

Retold by Martin Maudsley

Not

that long ago, many country folk in rural Dorset had to supplement their poorly-paid

income from labouring on farms by foraging for food and hunting

wild game in woodlands and common land: birds and deer, rabbits and hares;

whatever fare was there for the taking; always seasonal, not always legal. In

the village of Littlebredy there was a group of four men, four farmworkers, who

in the evenings hunted together – not with guns, they couldn’t afford them, nor

with nets that needed constant repairs – but with with hounds. Each man had his

own dog – a Longdog (an old Dorset

breed) – and in that ancient alliance, between human-kind and canine, the hunting

was a success; more often than not there was something to take home for the

pot.

On

days earmarked for hunting, after toiling in the fields from dawn and before setting

out with their dogs at dusk, the men were in the habit of leaving some their own

farm-working tools and agricultural equipment at the cottage of an old woman

who lived by herself in the Valley of Stones. Her house, and indeed the woman

herself, were so old and mysterious they seemed to have been there as long as

the ridgeway’s ancient stones and monuments. Well, there were some in the local

villages, suspicious and small-minded, who called the old woman a witch -

blamed her for all manner of malaises and mishaps. But there were others, too,

who beat a path to her door; who came to her for help in the secrecy of night. And

to all who came she listened with gentle wisdom, before offering herbal remedies

or healing words. The hunters themselves rarely saw the old woman, she was

often out at dusk, but they respected her and always made sure they left her a little

loaf of freshly-baked bread by way of thanks for looking after their tools.

One

evening, when the men were out hunting, just after harvest-time, they caught a

glimpse of a mysterious and magical creature – a pure white hare – racing over an

open field and before darting down the valley then disappearing into a copse of

trees. Well, they never got close to catching that hare; she was too cunning

for the hunters and too fast for their dogs. But men, sometimes, can be proud and

arrogant, and these men wanted to prove themselves as the best hunters. Over

the following days and weeks the hunters talked more and more of the elusive white

hare, and their burning ambition to catch it. They bided their time, and laid

their plans, like a spider weaving a web to catch a fly…

Soon

the pieces of their plan fell into place. On a moist and misty evening in September,

with a Harvest Moon rising huge and orange above the ridgeway, the white hare

was spotted nimbling along the edge of the copse. Some of the men sent their

dogs running through the trees to flush the hare out into the open. When the

hare saw the dogs she sturted and then ran

like lightening, zig-zagging across the adjacent field - ears flat against her

body, spine arching and stretching, back legs reaching beyond the front legs as

she pushed forward - her pace quickening all the time. Soon she’d outdistanced

the chasing dogs. But with the hounds behind her, she headed towards the only remaining

escape from the field – an open gateway in a thick hedgerow of hawthorn and

holly. The hare reached the gap ahead of the hounds. But there, hiding, on the

other side of the hedge, were two more men with two more dogs. As the white

hare ran past the dogs were leased from their leashes…

…The

still evening air was suddenly pierced with the sound of snapping teeth,

frenzied snarling and then a high-pitched, spine-tingling squeal. The dogs

ripped and wrenched, they bit and broke. Eventually the hare was tossed into

the air like a ragged doll; white fur flecked with red. She landed. Not back on

the ground, nor in the jaws of the dogs, but atop of the hedge. And although

badly hurt, and severely weakened, she summoned her remaining strength to

scamper painfully along the vicious vegetation of spikes and spines, until she

reached the safety of the woods and disappeared into the darkness of the trees.

Men

and dogs searched and sniffed for an hour, without sight or scent of the hare,

until the hunters finally admitted defeat. The dogs were taken back to their

tethers, and the men made their way to the old woman’s cottage to retrieve

their tools. When they arrived the door of the cottage was ajar, unusual, and

as they peered inside their faces drained of colour. There, lying on the floor

in a mangled heap, with torn clothes and broken, bleeding body, was the old woman.

Filled

with horror, the men grabbed their tools and ran from the cottage, pursued by

fear and guilt. All of them left. All except one, the youngest of the hunters.

The young man stepped inside the door. He bent down to the old woman and

realised that she was still breathing. Wrapping her in a woollen blanket, he lifted

her body, as light as bird, onto the bed and then held her head as he gave her sips

of water from a clay cup. All night long he stayed by her bedside. Eventually,

in the pale morning light, she opened her bruised eyes and was able to speak in

short breaths. She told the young man how to make a medicinal tea from hot

water and dried herbs in jars on the shelves around the room. He followed her

instructions, carefully and correctly, and in between brewing healing potions, he

went to fetch fresh food from the village. He stayed in the cottage for two

weeks, tending the old woman until she’d regained some of her strength and her

wounds were beginning to heal. Then she sat up, looked at him with smiling eyes,

and released him from his duties…

From

that day on the hunters of Littlebredy vowed never to hunt the white hare again.

Even today, long after the old woman’s death and her cottage long since crumbled

into broken rocks amongst the Valley of Stones, the story is still remembered.

And there are some Dorset folk that still gather each year, at dusk on a mild September’s

evening, in the hope of catching a glimpse of long ears and flashing fur - the

white hare, racing across the ancient fields around the ridgeway. If you’re

lucky, you might see her too…

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)